In the recent Victorian State Revenue Office statement summarising the outcome of the Optical Superstore litigation it was somewhat ironically noted “Essentially the contractor provisions are an elaborate set of definitions”.

Indeed they are.

In the recent Victorian State Revenue Office statement summarising the outcome of the Optical Superstore litigation it was somewhat ironically noted “Essentially the contractor provisions are an elaborate set of definitions”.

Indeed they are.

The Optical Superstore litigation involved enquiry as to how the Victorian relevant contract provisions applied to a scenario where an optometrist was contracted to provide services to patients at a facility conducted by a 3rd party. In broad terms, the commercial structure of the arrangement involved the optometrist ‘paying’ the facility provider a lease fee with the facility providing various services including collection of patient fees for subsequent remittance to the optometrist.

Much has been, and will be, written about the decisions that make up the litigation outcome (VCAT, Supreme Court, Court of Appeal and refusal of High Court to entertain an appeal).

In this article we will explore the implications of the litigation.

The outcome – follow the money

Most commercial arrangements where medical practitioners provide services at/through a 3rd party facility have historically been considered to sit outside of the ‘relevant contract’ rules (and hence not give rise to any PRT exposure). Relevant contract rules are contained in the payroll tax (PRT) legislation in all States/Territories except Western Australia.

Why?

It was considered the structure of the arrangement was not (albeit incorrectly as it now seems) a ‘relevant contract’ as defined.

For example, section 32 of the Victorian Payroll Tax Act 2007 (‘PRT Act’) defines a ‘relevant contact’ as:

- … a relevant contract in relation to a financial year is a contract under which a person (the designated person ) during that financial year, in the course of a business carried on by the designated person—

-

- supplies to another person services for or in relation to the performance of work; or

- has supplied to the designated person the services of persons for or in relation to the performance of work; …

-

It was commonly considered that the medical practitioner provided services to patients and received services from the facility provider and as such the ‘relevant contract’ rules were not engaged.

Even where a more sophisticated view of the reach of section 32 was applied, it was again commonly understood:

- there was no ‘payment’ from the facility provider to the practitioner where the facility was merely paying monies that ‘belonged’ to the practitioner (e.g. the practitioner patient fees net of any money due from the practitioner to the facility). If there was no payment there was no amount able to be deemed as wages.; and/or

- even if the remittance of the net monies was a payment, it was not “…for or in relation to the performance of work relating to a relevant contract” as is required by section 35 for an amount to be deemed as wages.

Post the litigation the common understanding has been squarely rejected, coming as a great surprise to many. However, apparently it was not a surprise to the Victorian State Revenue Office which noted in the decision impact summary:

The Commissioner’s view is that the Court of Appeal has interpreted section 35 (and section 3C(2)(c) of the Old Act) in a way that is consistent with the policy intention of the Acts.

It has always been the Commissioner’s position that the existence of a relevant contract needs to be assessed on a case by case basis. This is true of the criteria in section 32(1) as well as the exclusions from that definition in section 32(2) (and their equivalent sections in the Old Act), and the outcome in the Optical Superstore matter has not changed this position.

Now what?

The health industry is now grappling with the implications of the decision.

However, the principles of the decision will impact other industries/professions that operate on a similar model.

We now briefly consider the implications of the decision.

Implications

Significantly, the Optical Superstore outcome seems to be confined to PRT and, then, only to jurisdictions with relevant contract provisions like Victoria (e.g. everywhere except WA).

It appears the outcome should not change the income tax or superannuation treatment of the underlying payments. The legislative provisions regarding Pay As You Go Withholding and superannuation guarantee obligations turn on very different and less elaborate tests .

In relation to Workers Compensation, the situation is less clear given the divergent legislative approach to determining which relationships are within the scope of compensation and which amounts are treated as remuneration. Fundamentally, workers compensation legislation throughout Australia does not include ‘relevant contract’ style provisions.

Returning to the PRT position, the following matters appear to remain ‘open’ for discussion.

The brave hearted may seek to dispute an arrangement is a ‘relevant contract’. For example, the facility provider may dispute that it is supplied with “… the services of persons for or in relation to the performance of work“. Interestingly, it seems that Revenue Offices (Victorian and NSW at least) accept that a traditional service entity arrangement does not result in the medical practitioner providing services to the facility provider. These traditional arrangements are far less common today given the corporatisation of the health profession.

Little attention was paid in the litigation to exceptions contained in the ‘relevant contract’ rules.

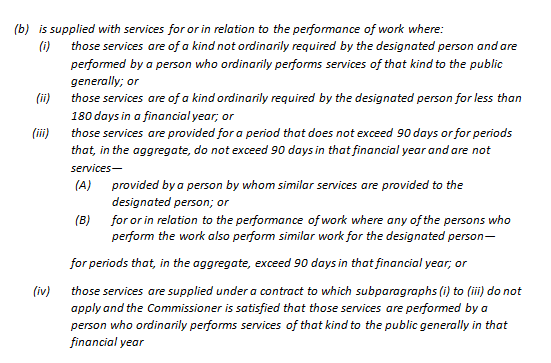

Under the exceptions, a prima facie ‘relevant contract’ ceases to be such where the services supplied fall within one of several categories. Using section 32(2)(b) of the Victorian PRT Act as an illustration of key categories, an exception may apply where the facility provider:

The application of the exceptions is heavily dependent on proof of factual circumstances and the onus of proof rests with the taxpayer.

Apart from the above evidentiary issue, application of the exceptions raise multiple practical issues:

For example, how broadly (or narrowly?) defined are ‘the services’ that should be considered when applying the exceptions. Consider a multi-disciplinary health facility where chiropractic services are offered 3 days a week only with other medical services available year round. Is it acceptable to treat the chiropractic service as a service distinct from other services provided at the facility?

Further, does a practitioner ‘…ordinarily performs services of that kind to the public generally in that financial year’ in the act of treating patients at a single medical facility or is it necessary for the practitioner to supply services to more than one facility and/or directly to patients (e.g. home visits).

Changing things up?

In terms of potential restructuring of arrangements, an obvious alteration to the fact pattern that may produce a different outcome is to ensure there is no remittance from the facility provider to the practitioner. For example, patient fees are banked to the account of the practitioner who is then responsible to pay any service charge due to the facility provider.

Alternatively, could the patient fee collection and ‘remittance’ to the practitioner be undertaken by a party other than the facility provider?

Whether it may be possible for the arrangements to be evidenced by way of a specific payment for the “…services of persons for or in relation to the performance of work” which is separate to the remittance of the patient fees is more problematic but should not be ruled out.

And so…

The PRT treatment applied should be revisited by any business paying amounts in circumstances similar to the Optical Superstore scenario.

This article provides a general summary of the subject covered and cannot be relied upon in relation to any specific instance. Webb Martin Consulting Pty Ltd and any person connected with its production disclaim any liability in connection with any use. It is not intended to be, nor should it be relied upon as, a substitute for professional advice.