This year has had many tax agents and business owners focusing on the immediate issues and support measures arising due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This has made it difficult to turn attention to the horizon and focus on some of the less immediate, but still worthwhile, issues and opportunities. With the lodgement due date for a significant number of clients’ 2020 income tax returns falling due in May 2021, practitioners (and their clients) may now be in a position to see how the ‘second wave’ of COVID-19 will pan out and the subsequent economic impact to their clients’ financial affairs for the 2021 year.

In this article we will briefly cover some tax focused opportunities and issues arising as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Superannuation contribution caps

With the ASX 300 index sitting just shy of 11% down as at 30 June 2020 when compared to 30 June 2019, the value of many superannuation accounts will likely have suffered a material decline. Such a decline may present an opportunity for individuals, whose Total Superannuation Balance (‘TSB’) was above $1.6 million at 30 June 2019, to make further non-concessional contributions to superannuation.

Generally, an individual’s non-concessional contributions cap is $100,000 per annum. In addition, an individual may be able to utilise the bring-forward rule to contribute up to an additional $200,000 in the same year.

However, an individual’s non-concessional contributions cap for a year is reduced to nil if their TSB equals or exceeds the general transfer balance cap (currently $1.6 million) just before the start of the current financial year. Similarly, the additional amount that can be contributed under the bring-forward rule is reduced by $100,000 or $200,000 where the member’s TSB equals or exceeds $1.4 million or $1.5 million, respectively.

For example, a superannuation member whose TSB was $1.65 million on 30 June 2019 suffered a decline in the market value of the underlying investments of $165,000, resulting in a TSB below $1.5 million. This would, subject to other contribution rules, allow the member to contribute up to $200,000 in the 2021 year by utilising the bring-forward rule (i.e. the member’s annual $100,000 non-concessional contributions cap plus an additional $100,000 under the bring-forward rule).

Understandably not everyone will be in a position to contribute such amounts to superannuation (especially given the potential impact of the pandemic). However, for those clients that may be in such a position, they and their advisers should determine, as soon as possible, whether their TSB has declined sufficiently to allow themselves the maximum amount of time to make a decision and/or free up cash. In deciding whether to make such contributions in the 2021 financial year consideration should be given as to whether the use of the bring-forward rule would be better utilised in the 2022 year (e.g. if markets decline further between now and 30 June 2021, this may allow for an increased amount to be contributed under the bring-forward rule in the 2022 year).

In addition, the principle considered above in relation to non-concessional contributions similarly applies to the unused concessional contributions cap carry-forward rule.

Under this rule the concessional contributions cap for individuals, whose TSB was below $500,000 at the end of the previous financial year, is increased by the five previous financial years’ unused concessional contributions cap (noting that only the unused concessional contributions cap for the 2019 financial year onwards can be carried forward). Accordingly, a decline in clients’ TSBs might result in some of those clients becoming eligible to make ‘additional’ concessional contributions for the 2021 financial year.

Division 7A

For taxpayers subject to a Division 7A complying loan agreement under section 109N, borrowers must make a minimum yearly repayment (‘MYR’) by the end of the relevant financial year, or the amount of the shortfall will give rise to an unfrankable deemed dividend.

For borrowers that were unable to make the full MYR for the 2020 financial year due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the ATO has implemented a streamlined process to apply for an extension of time to make the MYR for that year. This extension is limited to a maximum of 12 months and requires the catch-up MYR for the 2020 financial year to be made by 30 June 2021 in addition to the MYR for the 2021 year.

A separate application must be made in respect of each loan (regardless of whether they are all from the same lender) that borrowers wish to obtain an extension of time to make the MYR.

The Commissioner is only able to make a decision under section 109RD after the end of the year in which the MYR was required to be made so advisers need not worry that their clients have ‘missed the boat’. Applications made under the streamlined process can be expected to have a response within five business days of lodging.

Where the Commissioner applies his discretion to extend the amount of time under the streamlined process, no deemed dividend will arise in relation to the MYR shortfall for that loan, provided the MYR shortfall is paid by 30 June 2021.

If borrowers require more than 12 months to make the MYR for the 30 June 2020 year, they can make an application under section 109RD (outside the streamlined process) or alternatively, an application can be made under section 109Q for a deemed dividend not to arise on the grounds of undue hardship.

Further information about the streamlined process along with the request form can be found on the ATO website.

For clients that ordinarily meet their MYR obligations by offsetting their MYR against dividends declared by the lender, consideration should be given as to whether those clients’ taxable incomes will be reduced in the 2021 financial year. Depending on the quantum of any reduction, there may be an opportunity to declare a higher rate of dividends (replacing the forgone income) to make payments above the MYR for the 2021 financial year. This may result in more MYR repayments being made at lower tax brackets, reduced interest payable over the life of the loan and reduced tax payable on that interest.

We note that consideration also needs to be given to the company’s capacity to pay the dividends under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth).

Trading stock

Taxpayers who carry on a business are required to calculate the difference between the value of their opening and closing trading stock when determining their taxable income for the year. If the closing stock value exceeds the opening stock value, the excess is included in assessable income, alternatively if the opening stock value exceeds the closing stock value the excess may be deducted.

In determining the closing value of trading stock, for each item of trading stock a taxpayer may elect to use one of three valuation methods:

- cost;

- market selling value; or

- replacement value.

The ability to value each item of trading stock using one of the three methods affords taxpayers an opportunity to either bring forward or defer an amount used in the calculation of taxable income.

Whilst valuing stock at its cost would normally be expected to result in the lowest valuation, the impacts of COVID-19 may result in one of the other methods providing a lower valuation due to heavy discounting by retailers and suppliers during the pandemic.

Ordinarily clients would be inclined to opt for the methodology that provides the lowest valuation so as to reduce the tax cost in that particular financial year. However, dependent upon the extent to which COVID-19 has impacted a client’s business across both the 2020 and 2021 financial years to date (and its expected ongoing impact), advisers and clients may wish to consider whether bringing forward income or deferring a deduction may result in less tax payable overall across the two years (noting that advisers and clients will have a reasonable understanding of the impacts across both years by the time the 2020 income tax return is due for lodgement). Consideration should also go beyond tax payable and should also extend to whether the application of other provisions may give rise to negative outcomes (e.g. the trust loss and non-commercial loss provisions, or franking credits becoming ‘trapped’ in companies due to the reduction in the corporate tax rate for base rate entities effective from 1 July 2020).

Capital gains on shares – parcel picking

Continuing the theme of apportioning taxable income between various financial years, another potential option is in relation to capital gains. Due to cashflow issues clients may have disposed of shares, or alternatively may have timed the market well enough to have made substantial short-term gains from the March ‘dip’.

When taxpayers dispose of part of their shareholding in a particular company the ‘default position’ when choosing which parcels have been sold is to select the parcel(s) that result in the lowest tax cost in that financial year. Whilst advisers should ordinarily give consideration as to what further share transactions have arisen in the subsequent financial year at the time of preparing the tax return, due to the potential impact of COVID-19 on clients’ taxable incomes in the 2020 financial year it has become even more imperative to do so.

In these circumstance advisers may counterintuitively opt for parcels of shares that result in a greater tax cost in the 2020 year to ‘replace’ any lost or forgone assessable income and to utilise lower tax brackets. However, this should be subject to the following considerations (which are also relevant for non-pandemic years).

- Whether the selection of a particular parcel to minimise the current year’s tax would preclude a disposal in the following year from being eligible to use the general CGT discount (refer Example 1 below);

- Whether the selection of a particular parcel to minimise the current year’s tax will result in marginal tax rates being underutilised in a year where a holding consisting of parcels with disparate unrealised gains is disposed over successive years (refer Example 2 below);

- What further share transactions or other income that may arise in the financial year that may affect the above considerations.

Example 1

Individual Client A undertakes the following share transactions (please note: the historical share prices below are drawn from the actual prices of an ASX listed company over the same time period):

- Buy 2,000 Listed Co A on 27 September 2019 for $22.80 each (total $45,600);

- Buy 2,000 Listed Co A on 24 March 2020 for $11.04 each (total $22,080);

- Sell 2,000 Listed Co A on 12 May 2020 for $41.60 each (total $83,200);

- Sell 2,000 Listed Co A on 3 November 2020 for $71.00 each (total $142,000).

Overall Client A has made a combined gross capital gain of $157,520 over the 2020 and 2021 financial years. However, the combined net capital gain included in their assessable income across the two financial years is dependent upon which parcel of shares is selected for each disposal due to the possibility of applying the CGT discount to the latter disposal.

If Client A chooses the 27 September 2019 acquisition as being the parcel disposed in May 2020 (to reduce their tax cost in the 2020 year), their net capital gains for the 2020 and 2021 financial years will be $37,600 and $119,920 respectively for a total of $157,520 (due to the general CGT discount not being available on disposal of either parcel).

If Client A instead chooses the 24 March 2020 parcel as having been disposed of in May 2020, their net capital gains for the 2020 and 2021 financial years would be $61,120 and $48,200 respectively for a total of $109,320.

Whilst the latter scenario gives a higher taxable gain in the 2020 financial year, it results in an overall total net capital gain over the two years of $48,200 less than the former scenario.

Example 2

Individual Client B, whose salary and wage income is $150,000 p.a., undertakes the following share transactions:

- Buy 2,000 Listed Co A on 18 February 2020 for $39.87 each (total $79,740);

- Buy 2,000 Listed Co A on 24 March 2020 for $11.04 each (total $22,080);

- Sell 2,000 Listed Co A on 12 May 2020 for $41.60 each (total $83,200);

- Sell 2,000 Listed Co A on 21 July 2020 for $72.54 each (total $145,080).

Overall Client B has made a combined gross capital gain of $126,460 over the 2020 and 2021 financial years. As their other income is $150,000 Client B’s taxable income in at least one of those financial years will exceed $180,000.

If Client B chooses the 18 February 2020 acquisition as being the parcel disposed of in May 2020 (to reduce their tax cost in the 2020 year), their net capital gains for the 2020 and 2021 financial years will be $3,460 and $123,000 respectively. Of the total $126,460 of net capital gains across the two financial years, $93,000 will be taxed at the top marginal tax rate of 45% due to the other income of $150,000.

If Client B instead chooses the 24 March 2020 parcel as having been disposed of in May 2020, their net capital gains for the 2020 and 2021 years will be $61,120 and $65,340 respectively. Under this allocation, of the total $126,460 of net capital gains across the two financial years, only $66,460 will be taxed at the top marginal tax rate of 45% due to Client B being able to utilise the entirety of the $30,000 remaining under the 37% tax threshold in the 2020 financial year.

The latter scenario results in tax savings of approximately $2,100 over the two years.

The above examples highlight the importance (particularly given the effects of the pandemic) of considering the different options available and their outcomes when selling part of a shareholding.

Car expenses: log book method

Each year, numerous taxpayers claim a deduction for work-related car expenses. Under the log book method taxpayers determine their deductions by multiplying their business use percentage and the total car expenses incurred in the particular year.

Importantly, the business use percentage for a year is not simply the percentage recorded in a taxpayer’s log book.

The business use percentage for a particular period (usually the financial year) is calculated by dividing the business kilometres for that period by the total kilometres travelled in the period.

To calculate business kilometres for a particular period a taxpayer is required to make a reasonable estimate taking into account all relevant matters including the following:

- the business percentage contained in the logbook,

- any odometer records or other records they have;

- any variations in the pattern of use of the car; and

- any changes in the number of cars used in the course of producing their assessable income.

Ordinarily it would not be unreasonable for a taxpayer to estimate that the business kilometres for a particular year is equal to the product of the total kilometres travelled and the percentage of business kilometres recorded in their log book percentage (this is because any variations in the pattern of use of the car are arguably negligible). However, with many taxpayers having worked from home beginning from around March/April, along with many others reducing non work-related travel, their pattern of use of the car will have undoubtedly changed. As a result, work related car expense deductions calculated solely using the log book percentage will be inconsistent with the requirements of the law.

Taxpayers and their advisers will need to ensure they take into account the changed business use patterns when calculating car expenses.

Home office expenses

Given the forced shift to working from home across many industries, we must give mention to deductions relating to employees working from home. In April 2020, the Commissioner announced that taxpayers working from home would be able to apply a ‘shortcut’ method for calculating deductions for working from home expenses incurred between 1 March 2020 and 30 June 2020 (subsequently extended to 30 September 2020).

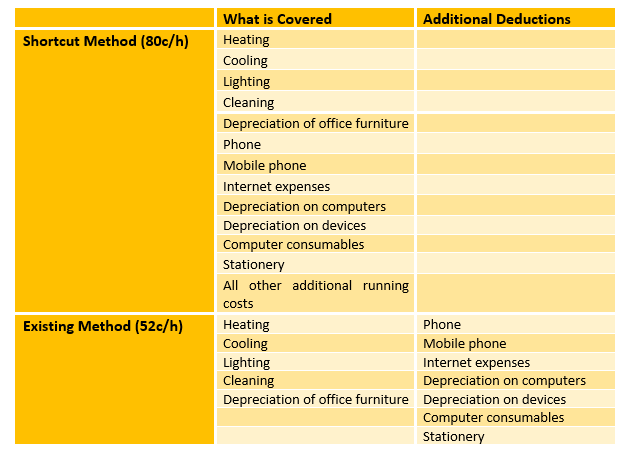

Using the shortcut method, which offers a higher rate of 80c/hr than the ‘existing’ method’s 52c/hr, may seem like an obvious choice, however, it is important to understand what expenses are covered by each method and therefore what other deductions are potentially forgone.

Given the above, a taxpayer may be able to obtain a much larger deduction by using the lower 52c/hr rate, which would allow them to claim the business portion of those other expenses identified in the table above that are not available under the 80c/hr rate. However, as taxpayers must have a dedicated work area, such as a home office, to use the 52c/hr rate, but no such requirement exists to use the 80c/hr rate and therefore its use may ultimately result in the greater deduction.

As the 80c/hr rate is only available from 1 March 2020, any work from home prior to this date will need to be calculated using the other methods available.

Taxpayers do also have the option of calculating their actual costs (apportioned for their private use) related to working from home instead of using the cents per hour rates.

Regardless of which method is used taxpayers need to ensure that they have met the record keeping requirements of that method. Additionally, taxpayers must have actually incurred additional expenditure to claim a deduction under any of the methods. Simply working from home without incurring any further expenditure (i.e. where an employer reimburses costs) does not entitle taxpayers to claim a deduction under the set rate methods.

Further information regarding working from home deductions is available from the ATO fact sheet and on the ATO website.

Fringe Benefits Tax

With the working locations and patterns of many employees having drastically changed, the default position on what benefits would ordinarily result in a Fringe Benefits Tax (‘FBT’) liability may be affected due to the operation of:

- the otherwise deductible rule, which reduces the taxable value of various fringe benefits by the amount that an employee would have been able to claim as a once off deduction had they incurred the expenditure; and

- the minor and infrequent benefits rule, which exempts certain benefits with a taxable value of less than $300 that are provided infrequently.

Advisers and their clients should take the time to review newly provided benefits (as a direct consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic) along with any benefits that have been historically provided. These benefits may now be subject to the above rules or a greater portion of the benefit may be disregarded or reduced.

Some examples of common benefits to give consideration to include:

- Work related travel reimbursements – travel to and from a workplace from home would normally be treated as a private expense. However, where an employee is primarily working from home, such travel (e.g. travelling to the office to attend a client meeting) may now be considered travel undertaken in the course of their employment as opposed to travelling to their place of employment. Accordingly, where an employer has reimbursed an employee for such travel this may trigger the application of the otherwise deductible rule and, therefore, not give rise to an FBT liability. We note the Commissioner’s views on employee travel in the context of FBT and income tax deductions are contained in TR 2017/D6 and TR 2019/D7.

- Home phone and internet expenses – it is not uncommon for some workplaces to reimburse directors and senior management for their home phone and internet expenses. Whilst these employees are working from home, the deductible portion of these expenses is likely to have increased.

- Work equipment – where work equipment has been provided to employees that is not subject to the electronic device exemption, the notional value of the fringe benefit may be under $300 and subject to the minor benefits exemption.

Furthermore, as numerous benefits and exemptions/concessions are determined with respect to where an employee’s place of employment is (an example being car parking fringe benefits and the car parking exemption) consideration should be given as to whether this place of employment has in fact changed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Where such a change has occurred, further consideration should be given to the impact on existing arrangements to determine whether those benefits should still be considered a fringe benefit or whether exemptions/concessions may now apply to those arrangements.

Conclusion

Whilst some of the above areas may not be relevant to all of your clients, this article will hopefully highlight the necessity to give consideration to a wider array of issues and opportunities to achieve the best outcomes for your clients and their affairs and to reiterate that tax planning is an ongoing and ever-changing process.

This article provides a general summary of the subject covered and cannot be relied upon in relation to any specific instance. Webb Martin Consulting Pty Ltd and any person connected with its production disclaim any liability in connection with any use. It is not intended to be, nor should it be relied upon as, a substitute for professional advice.